A Mighty Job for a Tiny Wasp

After nearly 15 years away, 2023 marked my long-awaited return to St. Helena, the island that shaped my childhood and became my heart’s home. This trip, however, wasn’t just about reconnecting with family and friends – it was also an opportunity to conduct my master’s thesis research on an invasive species threatening the island’s biodiversity: Wild Mango (Schinus terebinthifolia).

St. Helena Island, though small and remote, has always had an outsized role in my life. When I first arrived at age seven, the island and its people embraced me, and it became home. Now, as a researcher, I had the chance to return and give back by studying a key problem affecting the island.

If you’d like to read more about my time in St. Helena, click here.

The Wild Mango Invasion

One of the island’s biggest environmental challenges is the rapid spread of the invasive Wild Mango. For over a decade, this plant has threatened local ecosystems, agriculture, and even public health.

Traditional control methods haven’t succeeded, the spread is occurring too rapidly and the tree’s largest stands are often found in difficult-to-reach valleys. To combat this, researchers have been investigating biocontrol agents, like the chalcid wasp, Megastigmus transvaalensis, which has been utilised in other parts of the world as a means to limit the spread of Wild Mango.

The Mango Wasp

Megastigmus transvaalensis is a seed-chalcid wasp, non-native to St. Helena, that was first sighted on the island in 2020. Without a common name, the species was referred to as a “Mango Wasp” during my research due to its association with Wild Mango.

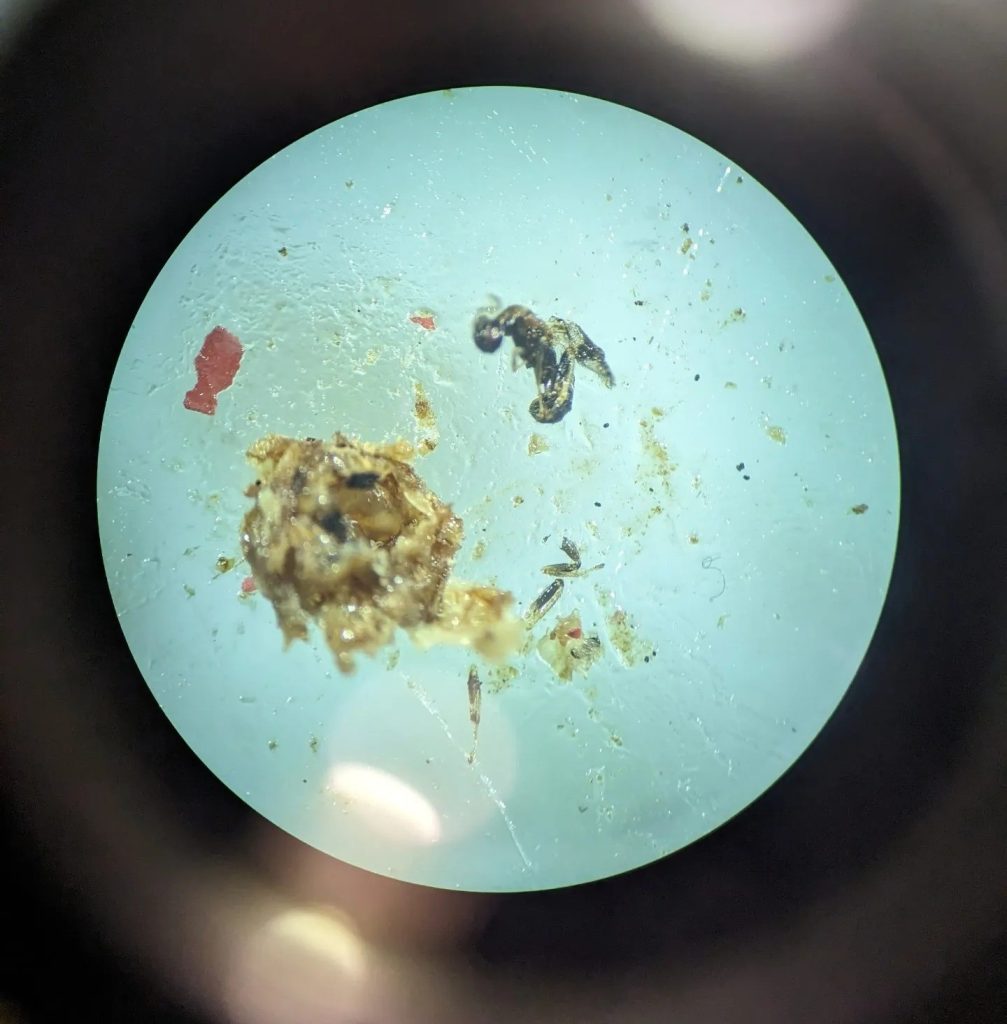

The Mango Wasp specifically targets the tree’s seeds by laying its eggs inside as they develop. Once the eggs hatch, the larvae feed on the seed’s internal tissue, preventing it from germinating. As the larvae grow, they eventually emerge from the seed, leaving small holes as evidence of their activity.

This process significantly reduces the tree’s ability to reproduce and spread. How significant this reduction truly is, is exactly what I intended to help determine.

Seeds, seeds, seeds

With my partner Jordan by my side, we collected Wild Mango seeds from five different locations around the island. Trekking for hours to reach deep valleys where the tree’s presence was most prominent and grabbing seeds from roadside verges and family gardens, we aimed for a variety of ecosystems.

Once enough samples were collected, my days were spent working in a makeshift lab, examining seeds for signs of wasp damage under a microscope. I checked each seed for the telltale emergence holes, where the Mango Wasp larvae had burrowed out after feeding. Seeds that didn’t show obvious signs of damage were dissected to determine whether live wasp larvae were still present inside.

Wasp attack

From these observations, I calculated the proportion of seeds damaged by the wasp – what we call the ‘attack rate.’ On average, about 42.6% of the seeds showed evidence of wasp presence, with some sites showing an attack rate as high as 76.2%.

While this was an encouraging sign that the Mango Wasp was indeed impacting the Wild Mango’s ability to reproduce, this percentage alone was unlikely to stop the tree’s spread entirely. For this to happen, an attack rate closer to 100% would likely be necessary. However, the presence of the wasp could act as a crucial ally in slowing down its rapid invasion, giving the island more time to employ additional management strategies.

The variation in attack rates across the island suggested that other factors – such as local environment, plant phenology (the timing of fruiting and flowering), or even climate – were influencing the effectiveness of the wasp. This highlighted the need for longer-term studies to fully understand how well the Mango Wasp could control Wild Mango in different parts of the island and whether other biocontrol agents might be needed to support its efforts.

Twists and turns

The study also revealed an unexpected twist: the wasp wasn’t just targeting Wild Mango. Although at much lower rates, it was also found to be infesting seeds of Schinus molle (Peppertree), a related species coexisting with Wild Mango in some areas.

This discovery hinted at the potential role of alternative host plants in sustaining the Mango Wasp population, especially when Wild Mango seeds were scarce. Further investigation into this relationship could help refine biocontrol strategies and reduce the risk of unintended consequences for other plant species on the island.

As my fieldwork came to an end, it became clear that while the Mango Wasp is unlikely to be a ‘silver bullet’ solution, it offers real hope in the battle against the invasive Wild Mango. With further research and integrated management approaches, St. Helena can better protect its unique ecosystems from the threat of invasive species.

Just the beginning…

Although the data I collected provided valuable insights, this research was quick, short-term, and really just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to understanding the Mango Wasp’s potential as a biocontrol agent on St. Helena.

The study took place over a few short weeks, and while I was able to identify an average attack rate of 42.6%, the real impact of the wasp on slowing the spread of Wild Mango requires far more extensive and long-term investigation.

In any biocontrol scenario, one season or snapshot of data is rarely enough to draw definitive conclusions. Ecological systems are incredibly complex, with factors like seasonal weather changes, tree phenology, and even the local presence of other species (like birds that could spread the seeds) all influencing outcomes over time.

The results of my study are promising, but they need to be taken with a pinch of salt. This wasp may prove effective in some areas or under certain conditions, but in others, it might not have as significant an impact.

To truly understand the potential of the Mango Wasp, further research is crucial. Long-term studies, monitoring attack rates across different seasons and varying environments, would help paint a clearer picture. Additionally, we need to explore the wasp’s interactions with other species, its adaptability to changing conditions, and whether there could be any unintended consequences on St. Helena’s native flora.

In short, while this study is a step in the right direction, there’s still a lot we don’t know – and a lot more work to be done to ensure the island’s unique ecosystems are preserved.

Thank you

I’d like to extend a huge thank you to those who helped make this research possible, including:

Dr. Stephen Compton

Dr. Roger Key

Rebecca Cairns-Wicks

St. Helena National Trust Staff

Rosie Peters

Jordan Warren

University of Leeds

Patsy Francis